The Impact of Covid-19 and Conflict on Middle Eastern Economies

Ten years after the outbreak of the Arab Spring, war, low oil prices and COVID-19 are affecting the economic situation of the Middle East. Conflicts continue in Syria, Libya and Yemen, while Iraq and Lebanon suffer from the breakdown of government authority. The region appears to be less affected by COVID-19 than others, but that may be because data on infections and deaths is incomplete.

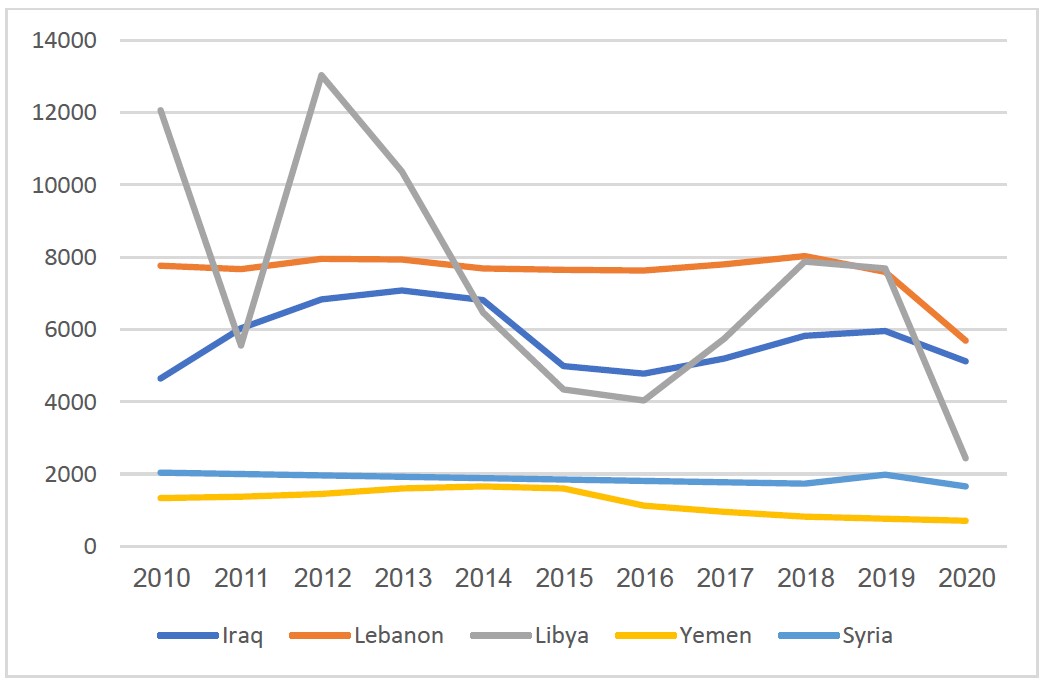

Chart 1 illustrates the falls in national income per capita that have been experienced in the last decade in the five countries that have suffered conflict or governmental collapse. It shows the combined effects of war, the decline of oil prices, political turmoil and demographic growth. The population of these five countries rose from 85 million in 2010 to an estimated 99 million in 2020 while their GDP fell by five percent in real terms. In Lebanon, Libya, Syria and Yemen, the fall in GDP was an estimated 43 percent.

Source: Author’s calculations from World Bank Data and World Bank, World Economic Outlook, October 2020

Syria

The war in Syria has been the most destructive conflict in the Middle East since the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s. Since the civil war began, the country’s demographic outlook has been transformed: between 2010 and 2018, there was a 20 per cent decline in the population, from 21 million to 16.9 million. If it had continued to increase at the pre-conflict annual average rate of nearly 2.67 per cent, then by 2018 it would have reached more than 26 million. The deviation from the no-conflict projection mainly reflects the huge of Syrians who fled the country. In 2019, more than 5.5 million Syrians were officially registered as refugees in neighboring countries. In addition, there were 790,000 Syrians in Germany and over 200,000 in other European countries.[1] By March 2020, the number of conflict-induced deaths was estimated at over 580,000.[2]

Between 2011 and 2018, total economic losses due to war in Syria were estimated at $442 billion. This is made up of the estimated value of the physical capital destruction ($118 billion) and estimated losses in GDP ($324 billion). Conflict-induced damage accumulated in seven of the most capital-intensive sectors: housing, mining, security, transport, manufacturing, electricity and health. Housing suffered the worst damage, at 17.5 percent of the total, followed by mining, at 16 percent. The security sector (military and police) was estimated to account for 15.3 percent of total physical damage, the transport sector reached 12.6 percent, while the manufacturing, electricity and health sectors accounted for 9.9 percent, 6.2 percent and 4.5 percent respectively. The education and tourism sectors accounted for 3.7 percent and 3 percent respectively.

By the end of 2018, real GDP was 46 percent of its 2010 level. The UN has calculated GDP losses by using counterfactuals. GDP is measured in the counterfactual scenario by assuming that Syrian GDP would have continued to grow after 2010 by an average annual rate of five percent, the average rate over the five years preceding the start of the conflict. As such, if the conflict had not taken place, Syrian GDP would have grown from $61 billion in 2010 to $90 billion by the end of 2018. The accumulated annual GDP loss is, therefore, estimated to have reached $324 billion by the end of 2018. As GDP does not, by definition, capture damage to physical capital outside the production process, the value of the damage to physical capital ($118 billion) has to be added to the GDP loss to reach an estimate of the total macroeconomic cost of the conflict of $442 billion.

In 2019, more than 11.7 million people in Syria were in need of at least one form of humanitarian assistance, with five million in acute need. Moreover, children constituted about 42 percent of those in need. This was significantly lower than the 13.1 million people in need in 2017, largely the result of the de-escalation of conflict in parts of the country.

Water, sanitation and hygiene protection and health were the three main categories in which need is pressing, with the number of vulnerable people exceeding 15.5, 13.2 and 13.2 million respectively. Nine million people have food security needs and another six million are in need of educational support. Almost 60 per cent of those in need were concentrated in the governorates that experienced intensified conflict, particularly Aleppo, Damascus and surrounding areas, and Idlib.

Water, sanitation and hygiene protection and health were the three main categories in which need was greatest, with the number of vulnerable people exceeding 15.5, 13.2 and 13.2 million, respectively. The assistance required across the remaining dimensions was also substantial, with nine million having food security needs and another six million in need of educational support. More than 59 percent of those in need are concentrated in the governorates that experienced intensified bloodshed and sustained sieges, particularly Aleppo, Damascus and Rural Damascus, and Idlib.[3]

Lebanon

On August 4, 2020, the Port of Beirut was the site of a massive explosion that killed around 200 people, wounded more than 6,000, and displaced more than 300,000 people in surrounding areas. The explosion resulted in an estimated $2.3 billion in damages and $241.8 million in immediate and short-term needs for recovery and reconstruction in the housing sector. Cultural and health institutions had estimated damage worth $1.2 billion and $115 million, respectively. Damage to tourism, as well as commerce and industry, was $205 million and $125 million, respectively; these sectors exhibited the largest immediate and short-term recovery and reconstruction needs, totaling $190 million and $185 million, respectively. Transport and port tops infrastructure sectors, with estimated damages of $345 million and immediate and short-term needs amounting to $470 million. The estimated damages of the governance sector are $80 million, with immediate and short-term needs for the recovery and reconstruction estimated at $198 million.

The explosion has exacerbated Lebanon’s pre-existing crises that have been in the making for several years. They stem from long-standing structural fiscal and external account imbalances and an overvalued currency, all sustained through sovereign debt issuance and financed by expatriate deposits. The long duration of the imbalances contributed to oversized bank balance sheets that had extensive exposure to government and central bank debt. The sudden stop in capital inflows during 2019 precipitated informal and ad hoc capital controls, depreciation of the exchange rate as well as the creation of multiple exchange rates, and the country’s first ever sovereign default on national debt obligations on March 7, 2020. On March 18, 2020, the government imposed a lockdown to counter the spread of COVID-19 including the closure of borders (airport, sea, and land) and of public and private institutions, exacerbating an already severe economic recession. The explosion destroyed physical and financial capital, slashed the purchasing power of wages and pensions, and deepened the country’s already significant poverty and inequality. With little domestic production in what is a highly dollarized economy, the sudden stop in capital flows led to a shortage of U.S. dollars that stifled trade and disrupted supply chains in virtually every sector. While the economy had already contracted by 1.9 percent in 2018 and 6.7 percent of GDP in 2019, the year 2020 will be the third consecutive annual contraction, projected at around 20 percent of GDP. Moreover, as the multiple exchange rates emerged, the Lebanese lira began trading at a discount of as much as 80 percent on the black market amid heavy fluctuations.

The explosion further exacerbated socioeconomic hardship, undermined trust in government, and increased the desire to emigrate. Prior the explosion, the fallout of the economic crisis and the pandemic had led to a significant increase in poverty and shrinking the middle class. Recent estimates suggest that poverty rates have leapt from 28 percent in 2019 to 55.3 percent in 2020, bringing the total number of poor in Lebanon to about 2.7 million. These socioeconomic deprivations have affected the relationship between people and the state. While trust in governmental institutions has been declining for years, the inadequate management of the impact of the explosion, combined with the economic crisis, has undermined trust even further. In a recent survey conducted by the World Bank among victims of the blast, the overwhelming majority of respondents reported having “no trust at all” in political parties, the Council for Development and Reconstruction, or municipalities. These developments increase pressures for emigration, especially among the middle class who represent much of the country’s human capital.[4]

Since the onset of the financial crisis in Lebanon in October 2019, the value of the Syrian pound has fallen dramatically. In June 2020, the Syrian pound heavily depreciated on the informal exchange market by 75 percent compared to October 2019 levels, reaching a peak monthly average value of SYP 2,505/USD. In October 2020, the monthly average exchange rate was recorded at SYP 2,339/USD, resulting in unprecedented increases in food prices.

Between January and June 2020, the national average World Food Program reference food basket price index increased by 124 percent and it was 240 percent higher than June 2019. The upward trend continued until October 2020, when the cost of the minimum food basket reached SYP 88,138 (the highest recorded ever in Syria since WFP price monitoring started in 2013). The upsurge in food prices reflected a similar trend of the share of households with poor food consumption, passing from 5 percent in May 2020 to 17 percent in October 2020.[5]

Unemployment rates in Lebanon rose from 6.2 percent in 2019 to 17.7 percent in 2020. Rapid inflation characterized the year 2020, with annual inflation rates averaging 73 percent in the first 10 months of the year. Since January 2020, inflation has steadily increased and peaked in October at 137 percent (compared with 1.3 percent in October 2019). The cost of the food basket increased by 116 percent between January and October 2020. In Beirut the food basket index was higher than the national average by 11 percent in the first 10 months of 2020.

Last year’s price spikes are mainly linked to exchange rate fluctuations and bank control mechanisms. However, in this very volatile economic context, Lebanon’s high dependency on food imports puts the country food insecurity at risk. In 2018, the country imported more than 80 percent of its wheat consumption, and food imports represented nearly 24 percent of total imports in the first half of 2020. With the current capital restrictions, many players abilities to purchase and replenish stocks are hampered and could lead soon to supply shortages, which are already observed in some parts of the country.[6]

Libya

According to the UN, 2011-2015 losses to the Libyan economy resulting from conflict totaled $216 billion. From 2016 to 2020, the cost of the war may have reached $364 billion and so the total cost of the conflict, from its outbreak in 2011 to 2020, is estimated at $580 billion. In the absence of a peace agreement in the coming years, the cost of the conflict will rise sharply. These very high losses were largely due to the loss of oil production and exports that dominate the economy. In 2010, oil production averaged 1.487 million barrels a day but by 2016 it had fallen to 389,000 barrels a day. The cost of continuing conflict between 2021 and 2025 is forecast at $465 billion, bringing the total cost of the conflict over the period 2011-2025 to $1.046 trillion.[7] One of the difficulties in predicting, or even imagining, a quick end to the conflict in Libya is the complex nature of the conflict, which has pitted regional rivals against each other in proxy warfare. The conflict, moreover, involves claims to gas reserves off the coast of Libya including the yet-to-be determined lines of demarcation in the sea between Libya and other states in the Mediterranean.

Yemen

Yemen has been affected by a number of conflicts that have crippled central governance, devastated the national economy, and exacerbated a longstanding humanitarian crisis. One estimate is that from the start of regional intervention in Yemen in March 2015 until November 2020, over 130,000 Yemenis had been killed.[8]

Between 2014 and 2019 Yemen’s GDP, measured in current prices, fell by 48 percent from $43.2 billion to $22.6 billion. Despite the conflict, the population grew from 25.8 million to 29.2 million, an increase of 12.2 percent. As a result, GDP per capita decreased by 55 percent from $1,673 to $774.[9]

Yemen is a low-income, food-deficit country, which produces merely 10 percent of its food and suffers chronically high levels of income poverty. After nearly six years of conflict and a series of consecutive crises, households have exhausted their coping strategies and have become extremely vulnerable to the slightest shocks affecting their ability to access food and other basic needs. The recent reduction in humanitarian assistance and the severe deterioration in economic conditions, along with the escalation of the conflict, were all compounded by the additional strains of COVID-19 on markets and livelihoods. In early January, the total number of reported COVID-19 cases reached 2,104 people with 611 deaths. The mortality rate was 29 percent, more than five times the global average and among the highest COVID-19 mortality rates in the world. Actual rates of infection and death rates are believed to be much higher than the reported rates.[10]

Iraq

Conflict in Iraq has left the country in a state of political paralysis and has had huge economic and social costs. In 2018, per capita GDP was 18–21 percent lower than it would have been if not for the conflict that began in 2014 with the rise of the Islamic State. Although Iraq’s oil GDP grew steadily during the conflict, nonoil GDP is estimated to be about 33 percent lower in 2018 than it would have been without the conflict, and has fallen below its peers. (The most dramatic and relevant comparison is with Iran, where the oil sector contracted but the non-oil sector grew). Iraq’s income from oil exports collapsed in 2020, but between 2010 and 2019 it earned about $720 billion from oil sales. This huge income has not been used to transform the economy: Iraq suffers chronic electricity shortages because the infrastructure is so bad. This is the result of mismanagement and massive corruption. As a result, the distribution of income is highly unequal.

According to the World Bank – even under a benign scenario – poverty in 2020 is estimated to have increased by between seven and 14 percentage points. This means that between 2.7 million to 5.5 million Iraqis would become poor, in addition to the existing 6.9 million poor.[11]

The poverty rate therefore increased from 17.5 percent to between 24 percent and 31 percent. An alternative estimate made by the UN, suggested that the poverty rate would double to 40 percent during 2020.[12]

COVID-19

The pandemic has taken a major toll on people in the East Mediterranean and has further devastated health systems, economies and communities, according to the WHO Regional Director for the region.

After reaching the second peak in week 47 (starting 22 November 2020) with more than 250,000 cases and 6,300 deaths, the Eastern Mediterranean Region experienced a decline in the number of reported cases and deaths with 155,300 cases and 3,046 deaths reported during week 53 (starting 27 December 2020). The situation varied widely between countries, with some showing a rising trend (e.g., Egypt and Bahrain), others are stabilized either at high level (e.g., Tunisia and United Arab Emirates), or low levels (e.g., Kuwait, Oman and Qatar), and the remaining experience a decline.

As of January 6, 2021, Iran has reported the highest number of cases in the Region (1,261,903 cases) followed by Iraq (599,965 cases) and Morocco (447,081 cases). Iran, Iraq, and Egypt reported the highest number of associated deaths.[13]

Recent updates from the World Bank on the impact of COVID-19 on the region have shown the effect of the crisis on the level of economic activity as estimates of economic growth were downgraded for 2020 and the impact of the changes in growth forecasts for 2021. The Middle East and North Africa’s 2020 GDP level was lowered by 7.5 percentage points on average compared with those made in December 2019. The largest GDP downgrade was for developing oil exporters (9.6 percent) followed by the GCC (7.4 percent) and developing oil importers (5.6 percentage points). These declines were the result of the COVID-19 pandemic and oil price collapse and were measured as a share of GDP in 2019.

The GDP losses estimated for 2020 increased as more information became available. Furthermore, the recovery in GDP level in 2021 is no longer expected to be a V-shaped but will be slower. The 2020 GDP level downgrade for MENA, using the baseline December 2019 forecasts, increased from 0.5 percent in March 2020 to 7.7 percent in October, 7.4 percent in November, and 7.5 percent in December. This trend reflects forecasters’ increasingly pessimistic view of the cost of the crisis during 2020.[14]

As a result of the pandemic, an estimated 14.3 million more people will fall into poverty, raising the total to 115 million people – slightly over 32 per cent of the population of the Arab middle-income and least developed countries. Increased poverty could also lead to an additional 1.9 million people becoming undernourished. Additionally, inflation is forecasted to rise sharply in 2020 in many countries; especially in Lebanon (32.8 percent), Iran (25.7 percent), Yemen (21.5 percent). Inflation is expected to continue rising sharply for those countries in 2021, with 18.9 percent in Lebanon, 19.6 percent in Iran, 11.7 percent in Yemen.[15] In December 2019 inflation in Syria was estimated at over 34 percent and conditions have deteriorated since then.[16]

[1] Federal Statistics Office (Germany), “Foreign population by sex and selected citizenships,” December 31, 2019; Zoe Todd, “By the numbers: Syrian refugees around the world,” PBS Frontline, November 19, 2019.

[2] Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, “Syrian Revolution NINE years on: 586,100 persons killed, and millions of Syrians displaced and injured,” March 14, 2020.

[3] UN Economic and Social Committee for West Asia, “Syria at War: Eight Years On,” 2020.

[4] World Bank Group, “Lebanon Reform, Recovery and Reconstruction Framework,” December 2020, full report can be downloaded here. See also, for example, Samia Nakhoul and Issam Abdallah, “Hundreds of disillusioned doctors leave Lebanon, in blow to healthcare,” Reuters, November 12, 2020.

[5] World Food Program, “Impact of COVID 19 in the Middle East, North Africa, Central Asia and Eastern Europe,” December 7, 2020.

[6] Ibid.

[7] UN Economic and Social Committee for West Asia, “Economic cost of the Libyan conflict Executive Summary,” 2020 edition, full report can be downloaded here.

[8] Congressional Research Service, Jeremy M. Sharp, “Yemen: Civil War and Regional Intervention,” December 8, 2020, full report can be downloaded here.

[10] World Food Program, “Impact of COVID 19 in the Middle East, North Africa, Central Asia and Eastern Europe,” December 7, 2020.

[11] World Bank Group, Middle East Region, “Iraq Economic Monitor,” Fall 2020, full report can be download here.

[12] Middle East Monitor, “United Nations expects poverty in Iraq to double to 40% in 2020,” May 14, 2020.

[13] World Health Organization, Regional office of the Eastern Mediterranean, “Five Million COVID-19 cases reported in WHO’s Eastern Mediterranean Region,” January 7, 2021.

[15] UN World Food Program, COVID-19 Regional Monitoring Hub – Cairo; see also, UN Economic and Social Committee for West Asia, “COVID-19, Conflict and Risks in the Arab Region Ending Hostilities and Investing in Peace,” November 17, 2020.

[16] The Syrian Observer, “Central Bank of Syria: Inflation Rate on the Rise,” November 27, 2020.